The Fundamentals of Coffee Tasting | Featuring Sensory Scientist Ida Steen

Perhaps you've experienced a moment when you taste a coffee and it distinctly reminds you of something—a blueberry, a rose, or maybe even a honeydew melon. Or, perhaps you haven't yet. If you identify with the former, its these moments, and unsuspected flavors that inspire intrigue into the potential of coffee.

Coffee is one of the most chemically complex things we consume, and as it would follow, beginning to identify subtle flavors in our morning cup can seem like a daunting task. Where exactly do we start? What are the fundamentals of coffee tasting? And, how can we become more perceptive?

This year has been an exciting one for the exploration of flavors in coffee. World Coffee Research published a Sensory Lexicon—a dictionary of coffee's flavors and their references—while teaming up with the Specialty Coffee Association of America to create the Coffee Taster's Flavor Wheel. But, what exactly is the significance of these documents? And, how can we use them to become better coffee tasters?

Today I am thrilled to share an interview with CoffeeMind's resident sensory scientist, Ida Steen, which explores a few of these essential questions about tasting coffee. Ida recently published a book called SCAE Sensory Foundation through CoffeeMind, and is presently teaching a Sensory Performance course at Square Mile Coffee Roasters in London. All this to say, Ida Steen knows a thing or two about the fundamentals of detecting flavors in coffee. I hope you will enjoy learning from her expertise as much as I have...

tLBCC: Can you share a little bit about your career in sensory science and coffee?

Ida Steen: As I have always been interested in the world of gastronomy, it seemed natural to me to study Gastronomy and Health with the focus of Sensory Science at the University of Copenhagen. During my studies I started a sensory project about coffee in cooperation with Morten Münchow—the owner of CoffeeMind—and for the first time I began to understand the amazing world of coffee. Coffee was something I decided I wanted to develop a deeper understanding of. I chose to write my master’s thesis about it, and this became the beginning of my increasing interest in coffee.

I am passionate about sensory science and have been the sensory scientist at CoffeeMind since 2014. I am currently researching an industrial Ph.D. project with the aim of investigating how to improve sensory performance using specific learning strategies. I am an Authorized Specialty Coffee Association of Europe (SCAE) Trainer (AST) in Sensory Skills and I am also involved in the SCAE sensory creators group. As CoffeeMind’s sensory scientist, I conduct research for industrial partners, train CoffeeMind’s sensory panel while teaching SCAE Sensory courses. I consult roaster start-ups and supervise students who carry out research on different aspects of coffee quality at The Department of Food Science in Copenhagen, Denmark.

tLBCC: What is the difference between taste and aroma?

Ida Steen: For me, the first and most important step into sensory science is understanding the difference between taste and aroma. A popular definition of taste is: the sensations in your mouth during eating. A good example of how this definition is used in everyday language is to say “this ice cream tastes like vanilla”. However, If you look at it scientifically the ice cream does not taste like vanilla. Instead, it has a vanilla aroma that is perceived by our retronasal system—which makes us think of it as a taste.

Taste is only what we perceive in our mouth as the five basic taste sensations; bitter, sweet, sour, salty and umami (savory). Whereas aroma can be perceived either as orthonasal, through our nasal cavity, or retronasal, through our oral cavity and up to the olfactory epithelium.

tLBCC: What exactly is a flavor?

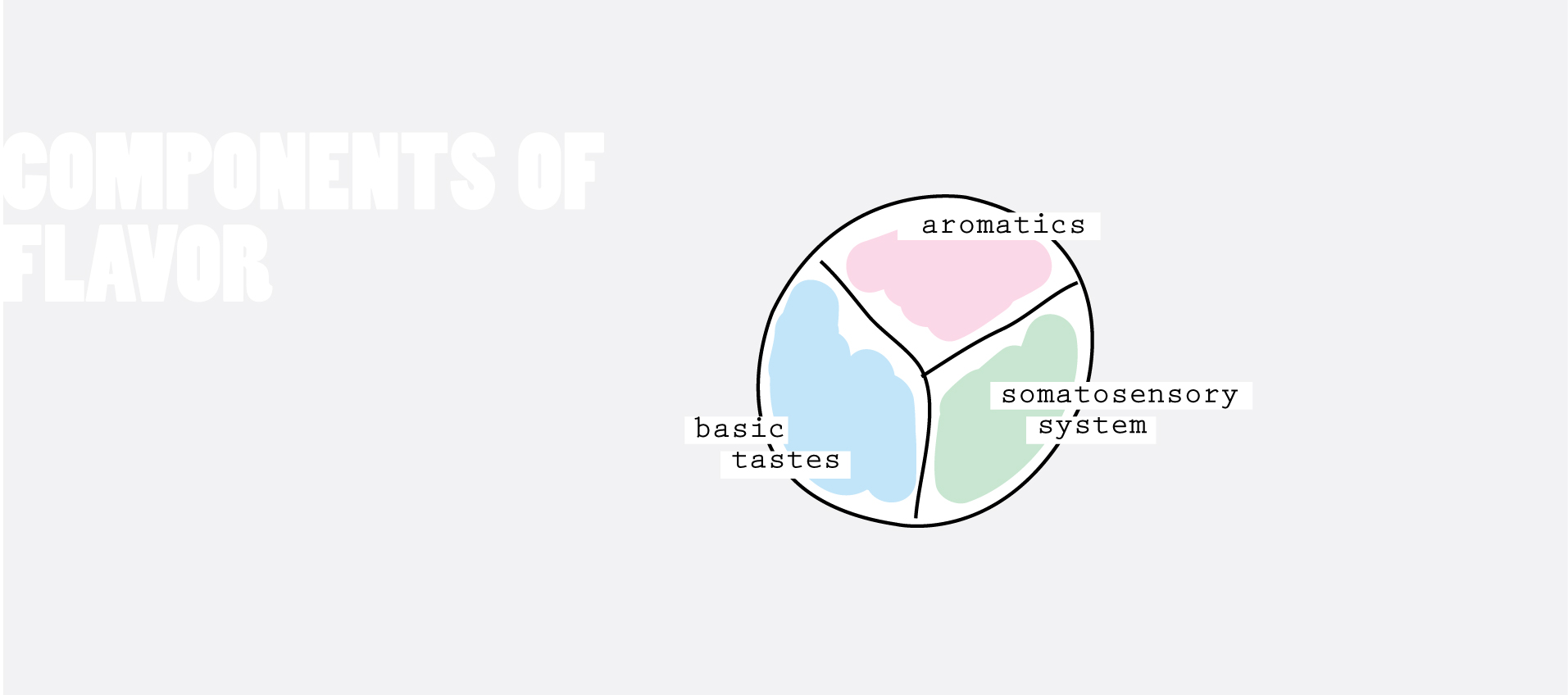

Ida Steen: This is a great question that I often hear! In the literature there are different opinions about what exactly should be included in the term flavor. In general flavor is a useful word that includes all the sensory impressions in the mouth. This means, if you describe the flavor of a cup of coffee, you are talking about the perceived combination of taste, aroma and mouthfeel. Some authors would even call flavor a multi-sensory experience and include the sense of sight and hearing as well. I like to consider the definition of flavor to include:

Aromatics: Olfactory (smell) perceptions caused by volatiles released from the coffee either by orthonasal (trough the nose) or retronasal (trough the mouth) detection.

Basic tastes: Gustatory (taste) perceptions caused by coffee in the mouth.

Somatosensory system: Chemical feelings that stimulate trigeminal nerve ends and include sensations such as astringent, pungent, spice, heat, cooling etc.

tLBCC: So, tasting a cup of coffee isn't as simple as it sounds. Can you explain the basic anatomy and physiology involved?

Ida Steen: I will try to explain it as simply as possible! When you take a sip of coffee the non-volatile compounds reach your taste buds, that are located on papillae on your tongue, these are the dots you can see. In the taste buds you find taste cells which contain receptors for the basic tastes. For example, when a bitter compound reaches a bitter receptor a signal is sent to the brain indicating that you are tasting something bitter.

The volatile compounds (the aromas) of the coffee are transported with air to the nose either orthonasal (by smelling) or retronasal (by tasting). In the nose they reach the olfactory bulb which contains multiple receptors for the aromas. The perception of aromas functions as pattern recognition, meaning that a single molecule aroma (e.g. vanilla) will activate one receptor that tells the brain that you smell vanilla. If the same molecule is combined with other molecules, more receptors are activated, and a completely different signal is send to the brain telling us that we smell something different. Coffee is a good example of a complex product containing many different molecules—this explains why coffee tasting requires a lot of training.

tLBCC: Are some of us naturally more talented at tasting than others? If we aren't born with this talent, do we have the ability to become more perceptive?

Ida Steen: Yes, it is definitely possible to train to become better! How you can train to improve your sensory skills—with the fastest and steepest learning curve possible—is exactly what I will be investigating in my Ph.D. project starting on the 1st of November. Here we want to investigate what specific learning strategies give the most significant effect on improving sensory performance. If you are interested in improving your own sensory skills, you are more than welcome to sign up for a Sensory Performance course and at the same time be a part of the research project (we need as many participants as possible).

In general there can be variations in odor and taste sensitivity. First of all, how sensitive we are is influenced by our degree of training or our exposure to, for example, coffee. Additionally there can be some genetic differences. As an example, we either have or don’t have the gene for detecting the bitter compound PTC. Biological aging can affect our sensitivity. From age 55 onward our number of taste papillae decrease, and there is also evidence of some decrease in olfactory sensitivity. Our nutritional state, certain medications, and pregnancy can also influence our sensitivity. Finally smoking is an issue. The good news is that there are no lasting effects on olfaction; we should recover after 30 minutes, but longer-term effects on bitter taste sensitivity are seen.

tLBCC: When first starting out, identifying flavors in coffee can be intimidating. Do you have any suggestions or simple exercises you'd recommend to experiment with at home that could build confidence and/or sensory skills?

Ida Steen: I would start by practicing the detection of taste and aroma in their pure form. You can do this by making a watery solution of each basic taste and ask a friend to cover different food products for you to detect by smelling (here you can get inspired by the descriptors in a flavor wheel). When you feel confident you can recognize all the basic tastes and a certain amount of aromas, you can start detecting them in coffee samples. You can even ask a friend to add taste and aromas to coffee in order for you to identify them.

Also, you can prepare sets of triangle tests to practice your ability to discriminate between samples. In the coffee business triangle tests are mostly known from cupping competitions, where a set of eight triangles need to be completed as fast as possible. In sensory science triangle tests are used for selecting qualified panelists for a particular test or to test whether there is a difference between two products. Triangle tests are also useful to determine whether shifts in processing or ingredients have significantly changed a product.

In a triangle test two of the samples are matching and one is different. Your task is to smell and taste the samples and detect the odd sample. You can use a test form like this:

tLBCC: A chapter in your newly published SCAE Sensory Foundation book is dedicated to the SCAA Flavor Wheel. Can you share a little bit about the significance of World Coffee Research's development of the Sensory Lexicon and the resulting Coffee Taster's Flavor Wheel?

Ida Steen: The World Coffee Research's Sensory Lexicon and the resulting Coffee Taster's Flavor Wheel is a purely descriptive tool and relies on sensory methodology, something I felt we were missing when I first started in the coffee business. Therefore these tools are bringing the coffee industry and the scientific world a little closer, which is also what we strive to do in CoffeeMind.

When performing descriptive tests where the aim is to describe the difference between coffee samples, it is important to calibrate the panel by using specific references. For example, if the coffee has a chocolate flavor, it is useful to have real chocolate as a reference to ensure agreement amongst the panel. For this approach, a flavor wheel can be a useful resource. Each descriptor on the SCAA Coffee Taster’s Flavor Wheel is found in the World Coffee Research Sensory Lexicon and by preparing these references there can be no doubt about what is meant by each descriptor.

When we are conducting a research project in CoffeeMind we develop a small sensory lexicon each time. The panel tastes the coffee samples included in the study, and decides what descriptors best describe the difference between the samples. Thereafter I find a reference for each chosen descriptor, and we train and calibrate based on these.

tLBCC: Since beginner coffee tasters may not have access to the SCAA's reference samples, is the flavor wheel still a useful tool for someone just starting out?

Ida Steen: It definitely is. You can use a flavor wheel for training purposes to detect the flavors in coffee. As a beginner I recommend you to start in the inner circle and practice detecting fruity, floral, chocolate, nutty, roasted, spicy, cereal and green aromas in coffee samples. Again, ask a friend to prepare references (use what you have in your kitchen) for you by assessing one category at a time. Make sure you are able to detect each descriptor in its pure form. When you feel confident that you can use these overall descriptors consistently, you are ready to detect them in coffee!

tLBCC: If Jane purchases a bag of beans from a local coffee shop that has tasting notes of raspberry, dried fig, and key lime, but she doesn't experience any of those flavors when she brews the coffee at home, does Jane have poor sensory skills? Or, what else could contribute to the discrepancies between the coffee roasters' specified tasting notes and what Jane tastes in her cup at home?

Ida Steen: That’s a very relevant question! Although I am afraid that I can’t give you a simple answer, since there can be many reasons for this—but I can try!

First of all, we don’t know how the descriptors on the bag were chosen. Were they mainly chosen for marketing purposes or are the descriptors actually present as aromas in the coffee? Was it only one person evaluating the coffee (who may have just eaten raspberries, and therefore the fruity aroma of the coffee caused this specific memory). Or did they set up an actual sensory profiling (blind tasting in triplicates, 10-12 panelists, randomized order, etc.). My guess is they didn’t! But, even if they did (or something similar), when conducting sensory analysis a varied response to the same stimulus should be expected among panelists. There can be a difference in the sensation they receive because their sense organs differ in sensitivity, or there can be a difference in the way their brains perceive the sensation. In other words, a person may not know a particular odor or taste, or could lack training in expressing what they sense in words and numbers. Through training, and with the use of references, the aim is for the panelists to move toward showing the same response to a given stimulus. Therefore what Jane can do is prepare a reference of raspberry, dried fig, and key lime, to see if it helps her detecting it in the coffee. If she still can’t, it is not necessarily because she has poor sensory skills. In general our perception of coffee can be influenced by many factors—the color of the bag, the lighting, the music, our mood, our previous experience, and so on.

tLBCC: Part of your work with CoffeeMind involves consulting roaster start-ups. What is one of the most common mistakes you see new roasters making when developing their sensory foundations?

Ida Steen: I always encourage people to taste their coffees blinded, preferably in a randomized order, and in replicates. In this way potential bias is avoided. Blind tastings reveal to what extent roasters are able to repeat their own scores. Randomization—preferably with the use of palate cleansers—avoids carry over effect from a previously tasted sample. For palate cleansers I recommend white bread, milk, and water or, for example, cucumber and sparkling water.

tLBCC: Are there any particular foods or substances you avoid to protect your coffee tasting instrument?

Ida Steen: Not in general, but at CoffeeMind we have a sensory panel that performs sensory profiling of coffee samples for research projects. I always tell the panel not to eat spicy food, drink coffee and tea, smoke, brush their teeth or chew gum two hours before a tasting session. This is for me, as a panel leader, to be certain that their palates are as clean, neutral, and as similar as possible.

tLBCC: Do you have a piece of advice to pass along to someone reading this that might be interested in pursuing a career in professional coffee tasting or sensory science?

Ida Steen: My best advice would be to start using your sensory skills in an active way. We tend to forget to notice all the sensory impressions we get throughout a day. As an example, imagine that you are cooking a tomato sauce. Very often we simply judge whether the sauce tastes good or bad. Instead, try to describe what you are smelling and tasting. Also, when you are eating lunch, riding a bike, or going for a walk, try to notice everything you smell—and don’t forget to put a name on it.

In general, we all have good odor memory. We can perfectly remember a smell, but a common problem is we tend to forget the name of the smell. Naming what we smell is exactly where we need to train to become better coffee tasters.

Also, sign up for a sensory course! That is always a great way to start a learning process.

tLBCC: Aside from your newly published book, you are currently teaching a Sensory Performance course at Square Mile Coffee Roasters in London during the month of September. Do you have any other upcoming classes, workshops, publications or collaborations we should know about?

Ida Steen: Yes we always have! I’m teaching a Sensory Performance course at CoffeeMind Academy in Copenhagen the 31st of October - 1st of November and again the 14th - 15th of December. Also, I’m teaching the SCAE Sensory courses regularly. You can see all the sensory courses we provide at CoffeeMind Academy HERE.

There is always the option for me to come to teach in your place, which can be of great value if you want you and your colleagues to work together as a sensory panel. During the Sensory Performance course you'll have your sensory skills mapped out. This means you will get to know your strengths and weaknesses, and can identify exactly how to train to become better.

Meet me at Nordic Roaster Forum where I will have a presentation on sensory methodology followed by a sensory profiling of a range of coffee samples.

I am currently writing a SCAE Intermediate book that will hopefully be ready in the near future. You can see all of CoffeeMind's books HERE.

I just got an article on coffee temperature accepted in the journal of Food Chemistry. Look out for that if you are interested in knowing what temperature you should taste your coffee!